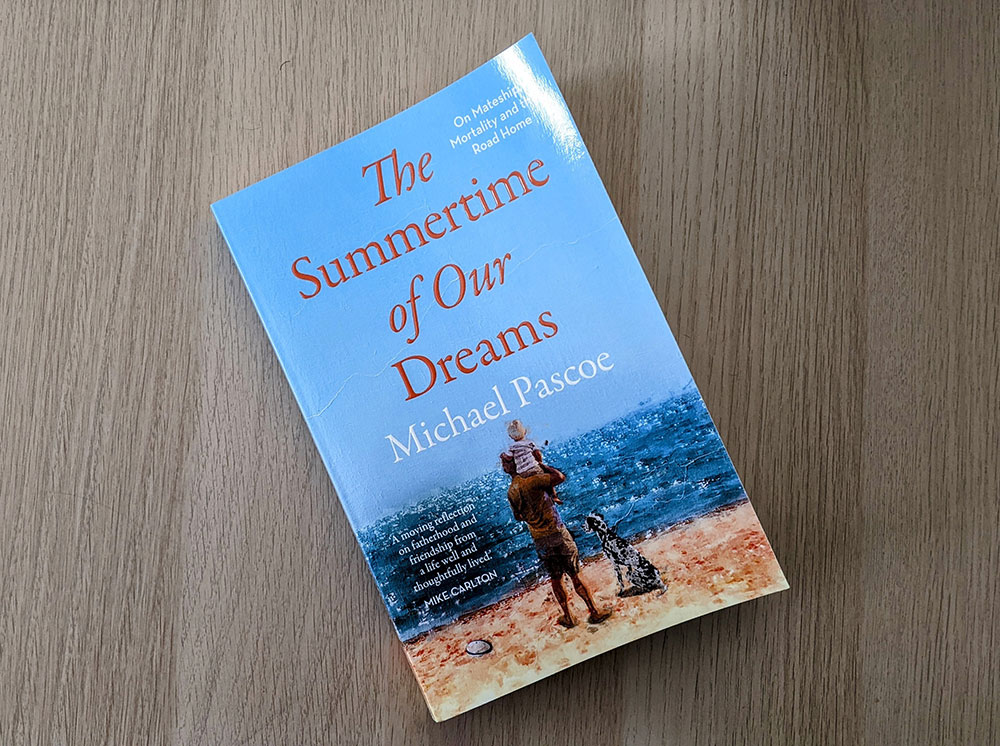

The Summertime of Our Dreams excerpt

An excerpt from The Summertime of Our Dreams by Michael Pascoe.

The Summertime of Our Dreams excerpt

An excerpt from The Summertime of Our Dreams by Michael Pascoe.

Come for a drive. It’s a good one if you like a drive, probably isn’t if you don’t. Too bad. Door’s open. Bit crowded but plenty of room. The car’s good. Actually, the car’s great. They’ve all been, they all are, whichever one we’re in. Measure your life by the car you were in at the time. Just go.

But you don’t really start a long drive when you start, even when it’s a metaphor, a skeleton upon which to hang your ghosts, a couple of particular drives amid a floating compilation of a lifetime’s driving and the last one.

Oh, you can be on your way, hopefully in the right direction, ordering your thoughts, but for the first bit your mind is back in the house. What did you have to do? What did you mean to do? Who were you supposed to call? Checked everything was turned off, the lights with the timers turned on? And did you bring everything you need? What have you left behind? You can be kilometres down the road before leaving the inertia of home. And then you can get ahead of yourself – when will you arrive? Will the entry permit at the Queensland border be OK?

Take the highway or Epping Road to Lane Cove Road quicker at this hour? The new toll road? That sort of thing.

It takes a little time to leave behind whatever you have left behind, to be on your way with this particular drive, to accept the solitude of your car and yourself and whatever scrapbook of your life you carry with you.

‘I am the Toad! The motor-car snatcher, the prison-breaker, the Toad who always escapes! Sit still, and you’ ll know what driving really is …’

Poop-poop.

But you can be unlucky, you can have the radio on for traffic news and they play The Proclaimers’ ‘I’m on My Way’. Turn the radio off but it continues, threatens to keep echoing between your ears from here to Queensland. Mentally overrule it with Talking Heads’ ‘Road to Nowhere’, settle in and finally start.

And take time.

Settle in to the time you have, the time to enjoy the experience of the car and the journey, the machine and movement, the kinetic wonder of landscape circling and wheeling, to feel the movement through the curve of your own space and time.

Some of us feel that more, some less, some not at all. From an age when the ability to drive was freedom and cars needed to be driven, when you felt and heard the partnership of car and driver, listened to the engine to be told to change gears, changed gears and told the engine, drove, drove into and through corners, up hills and as far as you cared, drove for the driving. You could fill a road trip’s soundtrack (cassette tapes before CDs before MP3s before Spotify on your phone) with odes to the automobile as means of escape, paeans to speed and life’s journeys.

Glad to be underway, to be away with the promise of the New England Highway and country and wide skies and an open twisting road rising and falling and your own thoughts.

Thoughts of the many times I’ve driven this thousand kilometres from Sydney to Brisbane over four decades. More than four decades.

The scrapbook’s pages flutter about as if I still have the Alfa Spider with the roof down, flap past the young couple’s annual pilgrimage in a Mitsubishi Sigma to visit family and their favourite beach. The young family, the madness of driving that far with babies and toddlers. The less young family requiring three rows of seats and teenagers’ boredom – the Peugeot 505 wagon, the Nimbus, the MPV, the big Chrysler Voyager. The couple again. A series of Alfas. By myself often enough.

Never by myself. Always company – the company of ghosts. What else be memories of life? Increasingly with ghosts and their intimations of mortality. A dose of DLBC lymphoma can do that to you as the time passes from the end of treatment, survival time the only measure of cure. The chemo leaving a damaged immune response with a virus about can do that to you, too. The scarring of a few years of caution.

With Jim now, with him whenever I’m out of the city by myself in the years since his death, but particularly this drive north and through his last country.

A strong ghost after our conversations about life and dying, never mind that we had said little or nothing to each other for most of our lives, reviving an unspoken brotherhood that outlives us in memories while memory itself changes.

It was a brotherhood that began as 13yearolds in 1969 on the Nudgee ‘flats’, half a dozen rugby fields that stretched away to the east down the hill from the first and second ovals, paddocks beyond them to a mangroved creek and swampy land, Nudgee Beach somewhere in the distance. The flats were a long way down from the Italian renaissance façade of St Joseph’s Nudgee College fronting Sandgate Road, the public image of an archbishop’s desire that ‘a residential College be made available for Catholic boys, especially those from country districts’. The Nudgee of 1891 in fields north of Brisbane a long way from the landmark GPS school now in the suburbs, blueandwhitestriped Edwardian blazers a long way from the ragtag soul of the flats.

Most boys started at Nudgee in Year 8 and had had a year to establish their hierarchies before the granting of conditional halffees allowed me to join them in Year 9, a solitary new boy to be assessed, measured for worth in the fit of the boarding school.

The 110 or so members of Year 9 were divided into three streams by the mix of subjects chosen. Jim and I didn’t overlap in any classes and played different summer sports – we might not have exchanged a word in the first term. Jim wasn’t a big talker anyway.

And then the rugby trials. Coaches might or might not correctly grade talent, a player can have lucky or unlucky trials, but the boys know soon enough. I was in the under 14Bs for the first game. The 14As barely won a lineout that Saturday and Rollo broke his collarbone, a combination that elevated the new boy. I can see 13yearold Jim, already a quality backrower, assessing the tall, skinny second rower, quickly knowing my strengths and weaknesses, accepting them as we trained three afternoons a week, fought the enemy on Saturdays and played touch or tackle among ourselves the rest of the time for the next four years and in the athletics team together as well, building complete trust. Easygoing mates trained to the point of instinct to cover, to assist, to help as bodies collide and fall.

After my final Year 12 exam, I didn’t see or talk to Jim for 30 years.

I’m remembering childhood and youth more, remembering mistakes and regrets more while decades of adulthood, of ‘success’, feature little. Adult failures, too – there are more of them. From mistakes made in selecting this or that boy for a junior representative team to words left unsaid, or said when they should not have been, they float back unbidden.

And whole decades can go largely missing. I am reminded by grandchildren now that so much time must have been spent with the boys when they were small, so many beach holidays, and they’re not recalled in more than flashes, can’t be dialled up to be rerun, to be savoured. So much time lost, decades disappeared. Tidying some of her mother’s jumble, Judy found a photograph of me with the older three on a beach, a young man with a reddishbrown beard and three beautiful blond boys. I would relive that day on a beach over and over forever – but I can’t.

It would be a worry if I worried about such things, so I don’t. Jim, getting closer to death, told me he was spending more time with his early days, of the surprise he had in feeling an almost overwhelming happiness when visited by someone from his wild bush youth.

‘Memory is a funny thing, Michael,’ he said.

The Summertime of Our Dreams

Michael Pascoe

Trade Paperback

RRP $34.99

Related topics

Things to note

The information in this article has been prepared for general information purposes only and is not intended as legal advice or specific advice to any particular person. Any advice contained in the document is general advice, not intended as legal advice or professional advice and does not take into account any person’s particular circumstances. Before acting on anything based on this advice you should consider its appropriateness to you, having regard to your objectives and needs.